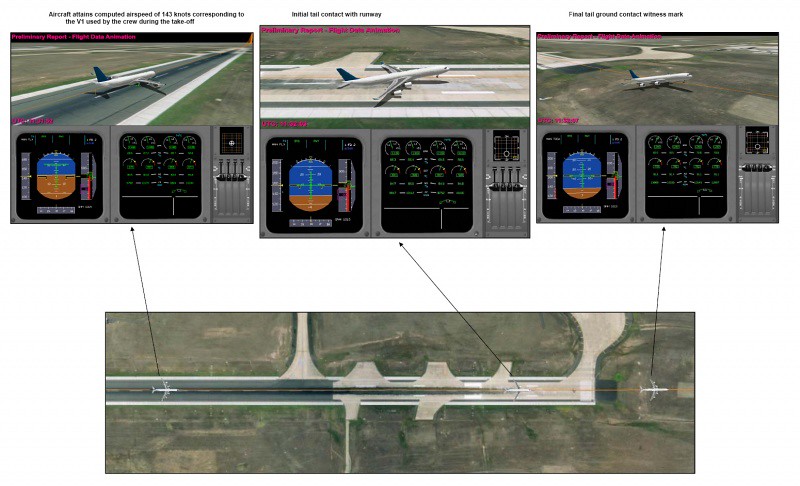

Figure 1 – Graphical representation of Digital Aircraft Condition Monitoring System Recorder (DAR) data showing position of aircraft at a computed airspeed corresponding to V1 used by the crew, initial tail contact with ground, and final tail ground contact witness mark. Source: ATSB AO-2009-012 Final Report.

| Event Details | |

|---|---|

| When | March 2009 |

| Event Type | HF, RE |

| Day/Night | Night |

| Flight Conditions | On Ground – Normal Visibility |

| Flight Details | |

|---|---|

| Aircraft | AIRBUS A-340-500 |

| Operator | Emirates |

| Domicile | United Arab Emirates |

| Type of Flight | Public Transport (Passenger) |

| Origin | Melbourne |

| Intended Destination | Dubai |

| Actual Destination | Melbourne |

| Flight Phase | Take Off |

| TOF | |

| Location – Airport | |

|---|---|

| Airport | Melbourne |

| General | |

|---|---|

| Tag(s) | Flight Crew Training Extra flight crew (no training) Inadequate Aircraft Operator Procedures |

| HF | |

|---|---|

| Tag(s) | Distraction Ineffective Monitoring Data use error Procedural non compliance Gross Data Error not recognised |

| RE | |

|---|---|

| Tag(s) | Overrun on Take Off Unable to rotate at VR |

| EPR | |

|---|---|

| Tag(s) | PAN declaration |

| Outcome | |

|---|---|

| Damage or injury | Yes |

| Aircraft damage | Minor |

| Non-aircraft damage | Yes |

| Causal Factor Group(s) | |

|---|---|

| Group(s) | Aircraft Operation |

| Safety Recommendation(s) | |

|---|---|

| Group(s) | Aircraft Operation Aircraft Airworthiness |

| Investigation Type | |

|---|---|

| Type | Independent |

Description

On 20 March 2009 an Airbus A340-500 being operated by Emirates Airline on a scheduled passenger flight from Melbourne to Dubai with an augmented (relief) crew occupying the two flight deck observer seats suffered a tail strike and did not become airborne until after the end of take off runway 16 at Melbourne at night in normal ground visibility. Only subsequently, when an ECAM (Electronic Centralized Aircraft Monitoring) annunciation of a tail strike was apparent and ATC called, did the crew realise that a tail strike and overrun had occurred and it was decided to return to land to "assess the damage" with a 'PAN' was subsequently declared. An unusual noise accompanied by a cabin report of smoke in the rear cabin area just after completion of fuel dumping led to a precautionary request to ATC for a landing as soon as possible but a full inspection after coming to a stop on the runway founds no signs of fire and a normal taxi in to a gate was then made for disembarkation. None of the 275 occupants were injured but the aircraft rear lower fuselage and ground installations beyond the end of the departure runway struck by it were damaged.

Investigation

An Investigation was carried out by the Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB). FDR data recording was found to have ceased as the aircraft had become airborne and this was attributed to the dislodgement of the FDR from its mounting rack immediately behind the rear pressure bulkhead to where it was found after the flight, lying (undamaged) on the lower fuselage skin below and slightly to the rear of the mounting rack. Fortunately, a DAR (Digital ACMS Recorder) was also fitted and had recorded most of the FDR parameters as well as others in Non-Volatile Memory (NVM).

The trajectory of the aircraft during the take off was established from the evidence available. The aircraft rear lower fuselage had contacted the 3657 metre long runway at three locations, starting at 265 metres, 173 metres and 110 metres from the end of the runway. It had then overrun the end of the runway onto the stopway and across the grassed clearway, becoming airborne three seconds after the selection of TOGA thrust. However, before gaining altitude, the aircraft had struck a Runway 34 lead-in sequence strobe light and several antennae, the latter impacts having disabled the Runway 16 ILS. A small depression at the end of the 60 metre stopway had resulted in the rear fuselage briefly losing contact with the ground and the final ground contact mark had ended 148 metres beyond the end of the paved runway surface (and beyond the 120 metre Clearway).

Inspection of the aircraft lower rear fuselage found the lower skin to have been abraded by contact with the runway surface and in some areas worn through its full thickness with grass and soil caught in the airframe structure. One service panel had been dislodged and was subsequently found beyond the end of the take off runway along with numerous pieces of metal from the abraded skin panels.

It was established that performance calculations for the take off had been made using the Airbus Less Paper Cockpit (LPC) system on a single EFB. In accordance with the Operator's SOP, the second EFB carried was used only as a backup in the event of a malfunction in the one being used. An aircraft take off weight of 100 tonnes less than the actual weight available to the flight crew was inadvertently entered into the EFB and the effects of that error on speeds and thrust settings were not subsequently noticed by any of the four pilots present. When the aircraft failed to become airborne after two 'Rotate' calls using the reduced thrust calculated, the aircraft commander had applied TOGA thrust and a few seconds later the aircraft had become airborne. Whilst still airborne, the crew had established for themselves the origin of the difficulty getting airborne as the gross error in the entered take off weight when the EFB was accessed to begin the landing performance calculations.

The Investigation found that there had been a complete failure of the procedural cross checks to detect the gross error of weight or its effects. The operating First Officer, who had also been PF for the take off, was found to have made the initial weight input error and the required cross check by the aircraft commander of the take-off weight in the FMGS with that used in the take-off performance calculation was then not made. The aircraft commander had entered the EFB performance figures into the FMGS and crosschecked them with the First Officer against the erroneous values that had previously been copied onto the flight plan. He had then handed the EFB back to the First Officer, who had stowed it before they completed the loadsheet confirmation procedure together. During that procedure, it was found that the First Officer had correctly read the weight from the FMGS as 361.9 tonnes but, when reading the same weight from the flight plan, had stated 326.9 tonnes before immediately correcting this to 362.9 tonnes. This procedure also included the First Officer reading out the (wrongly recorded) 'green dot speed' (best speed for climb once clean, affected only by aircraft weight and altitude) of 265 knots490.78 km/h

136.21 m/s from the FMGS which was accepted by the aircraft commander.

During the take off roll, using an assumed temperature calculation of reduced thrust which had been produced using the wrong (low) take off weight, the rate of acceleration had not been perceived as lower than required. The rotation rate used was found to have been as prescribed and the tail strike had been the result of continued rotation following the second 'rotate' call which led to the aircraft reaching the geometric limit of 9.5° after which TOGA thrust was applied. It was considered "unlikely that the flight crew had time to recognise that the aircraft had not lifted off at the expected pitch attitude of about 8°." In this respect, it was noted that, at the prevailing rotation rate, it would have taken only about half a second to increase the pitch by 1.5°, making the PFD an ineffective means of identifying the exceedence.

It was noted that, whilst climbing to 7000 feet2,133.6 m to commence fuel dumping, it had become apparent that the aircraft was not pressurising. No specific reason could be established for the apparent sight and smell of smoke in the rear cabin that had accompanied it but it was considered that the change in aircraft attitude as descent was commenced probably led to dust and odours from the earlier damage.

The Investigation distinguished two aspects of the accident as:

- the over rotation which led to the tail strike

- the long take off roll which led to the overrun

The Investigation examined in detail the ways in which a number of cross checks built in to the procedures for establishing take off data had all failed. The "lack of recognition of the degraded take off performance (relative to that needed) until very late in the take off run" was considered to have compounded the use of erroneous take off data which had created the conditions for the accident. However, it was noted that pilots rated for mixed fleet operations, as in this case for the A330-200, A340-300 and A340-500, there was an exposure to a large range of take off weights and (perceived) accelerations. Given that distraction was considered to have played a major part in facilitating error, a detailed examination of the effectiveness of risk management in this area was made. It was considered that:

- The operator had identified other flight phases as critical to the safety of flight, such as taxi, takeoff and climb, and had a sterile cockpit rule for those phases. There was no such management practice to reduce the potential for distraction during the take-off performance calculation and checking process.

- The provision by the operator of briefings to flight crews on distraction management in the months prior to the accident appear to have been ineffective in this accident.

In respect of the augmenting crew, it was considered that:

- The lack of clear direction on the role of, and required input from the augmenting crew during the pre-departure preparation further increased the distraction risk to the operating flight crew.

- The presence of augmenting crew in the cockpit during the pre-departure phase (in itself) created a distraction for the operating crew.

In respect of the SOPs involved, there was concern that, as usual, they were "typically designed on the basis that information flow….is sequential and….procedures are conducted in a linear fashion based on this sequential information flow" whereas research has shown such a linear flow is atypical in line operations which "increases the likelihood that, following a distraction, the flight crew will re-enter a procedure at an incorrect point."

It was concluded after eliminating all other possible causes and establishing the chain of events with all the available evidence that "the over rotation and tail strike were due to the incorrect rotation speed and flap configuration for the actual weight of the aircraft".

The preface to the Findings included the remarks that "although there are a number of factors identified directly relating to this accident, the accident needs to be taken in the context of the long history of similar take-off performance events." Consequently, the recommended safety responses as result of the Investigation are "those that address the whole situation, not just those that address the specific factors identified in this accident".

Five Safety Issues were identified:

- The existing take-off certification standards, which were based on the attainment of the take-off reference speeds, and flight crew training that was based on the monitoring of and responding to those speeds, did not provide crews with a means to detect degraded take-off acceleration. [Significant safety issue]

- The operator's training and processes in place to enable flight crew to manage distractions during the pre-departure phase did not minimise the effect of distraction during safety critical tasks. [Significant safety issue]

- The available Cross Crew Qualification and Mixed Fleet Flying guidance did not address how flight crew might form an expectation, or conduct a 'reasonableness' check of the speed/weight relationship for their aircraft during takeoff. [Significant safety issue]

- The failure of the digital flight data recorder (DFDR) rack during the tailstrike prevented the DFDR from recording subsequent flight parameters. [Minor safety issue]

- The lack of a designated position in the pre-flight documentation to record the green dot speed precipitated a number of informal methods of recording that value, lessening the effectiveness of the green dot check within the loadsheet confirmation procedure. [Minor safety issue]

Safety Action in response to the accident and the investigation of it by the ATSB itself in initiating and completing a Safety Study on "Take-off performance parameter errors: A global perspective" was noted. After taking account of Safety Action by Emirates, Airbus, EASA and FAA as described in the Report, the ATSB made one Safety Recommendation:

- That the FAA take action to address the existing take-off certification standards, which are based on the attainment of the take-off reference speeds, and flight crew training that was based on the monitoring of and responding to those speeds, and do not provide crews with a means to detect degraded take-off acceleration. (AO-2009-012-SR-079)

In respect of the outstanding concern about the issues raised by 'Cross Crew Qualification and Mixed Fleet Flying' the Investigation determined that the best way to progress this matter was to direct 'Safety Advisory Notices' to the FSF and to IATA requesting respectively that:

- The Flight Safety Foundation consider developing guidance to assist flight crews form appropriate mental models in respect of the weight and corresponding take-off performance parameters for a particular flight. The use by operators of mixed fleet flying increases the importance of that guidance. (AO-2009-012-SAN-086)

- The International Air Transport Association to encourage its members to develop guidance to assist their flight crews form appropriate mental models in respect of the weight and corresponding take-off performance parameters for a particular flight. The application by operators of mixed fleet flying increases the need for that guidance. (AO-2009-012-SAN-087)

The Final Report of the Investigation was published on 16 December 2011: Aviation Occurrence Investigation AO-2009-012 Final.